Vanilla JS information pages

publishing an API on a web page with plain old JavaScript 2025-01-21 #collaboration

- Appsmith

- Superblocks

- Retool

- JavaScript code ←

Each article in this series builds a three-page sample application, This article takes a different approach to the low-code application builders, implementing the same example application in JavaScript code.

For simplicity, this example has no code dependencies – third-party helper code. A real application would use third-party libraries for some functionality, such as a more sophisticated table component, or for API authentication.

Example application

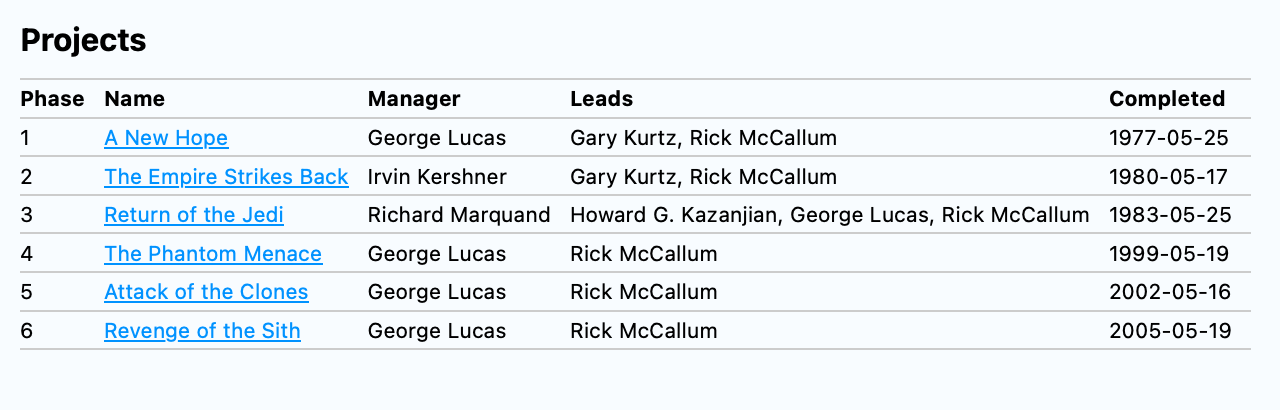

In this example application, the projects table uses a plain HTML table:

Six ‘projects’ don’t need sorting and filtering; a table with more data could use the DataTables component.

The table’s plain HTML links link to the project details page, which uses an HTML list of project roles, unlike the app builders complex list components:

Each role links to the role details page:

Again, this page uses a plain HTML table to display the role’s properties.

Projects table

The user-interface uses minimal HTML, with a separate style sheet (source code):

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Projects</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="projects.css">

<script src="projects.js"></script>

</head>

<body onload="renderProjects()">

<h1>Projects</h1>

<table>

<thead>

<tr><th>Phase</th><th>Name</th><th>Manager</th><th>Leads</th><th>Completed</th></tr>

</thead>

<tbody></tbody>

</table>

</body>

</html>

When the page has loaded, the renderProjects JavaScript function populates the empty table body,

with a fetchJson helper function for the API call:

// Populates the table body with films data.

const renderProjects = () => {

const tbody = document.querySelector('tbody')

fetchJson('films.json').then(films => {

films.forEach(film => {

const tr = document.createElement('tr')

tr.innerHTML = `

<td>${film.id}</td>

<td><a href="project.html#${film.id}">${film.title}</a></td>

<td>${film.director}</td>

<td>${film.producer}</td>

<td>${film.released}</td>`

tbody.appendChild(tr)

})

})

.catch(renderError)

}

The line that sets each new table row’s innerHTML holds the key to this code,

using an inline template for the HTML td elements, and interpolated values.

Note also the film ID in the linked URL hash (a.k.a. fragment identifier), e.g. project.html#1,

which the project details page will use in the API call.

This version uses simpler JSON than the earlier articles, which demonstrated JavaScript code to transform the API’s JSON responses. However, that wouldn’t change this JavaScript code much.

The fetchJson helper function, which each page uses, wraps the JavaScript fetch API,

and logs the HTTP response status:

// Returns a JSON promise for data fetched from the given URL by HTTP.

const fetchJson = (url) => {

return fetch(url)

.then(response => {

if (response.ok) {

console.log(`GET ${url}\n${response.status} ${response.statusText}`)

}

else {

throw new Error(` GET ${url}\nResponse: ${response.status} ${response.statusText}`);

}

return response.json()

})

}

If the API call fails, the renderProjects function handles the error and delegates to a renderError function that logs the error and displays a simple error page:

const renderError = error => {

console.error(error)

const body = document.querySelector('body')

body.innerHTML = ''

body.className = 'error'

}

Project details

The project details page works the same way, this time with id attributes on the elements to populate,

so the JavaScript templating doesn’t hard-code the tag name:

<h1 id="name"></h1>

<section>

<h2>Context</h2>

<pre id="context"></pre>

</section>

<section>

<h2>Roles</h2>

<ul id="roles"></ul>

</section>

As before, the renderProject function uses fetchJson for the API call,

using the ID from the URL hash in the JSON data URL, e.g. film/1.json:

// Populates the title h1, opening crawl paragraph, and roles list

const renderProject = () => {

const filmId = window.location.hash.replace('#', '')

fetchJson(`film/${filmId}.json`).then(film => {

document.title = `${film.title} – Project`

document.querySelector('#name').textContent = `Phase ${film.episode}: ${film.title}`

document.querySelector('#context').textContent = film.opening_crawl

const roles = document.querySelector('#roles')

film.characters.forEach(person => {

const li = document.createElement('li')

li.innerHTML = `<a href="role.html#${person.id}">${person.name}</a>`

roles.appendChild(li)

})

})

.catch(renderError)

}

As well as populating the contents of the #name, #context and #roles elements,

this render function sets the HTML document title,

so that the browser history doesn’t show the same page title for every project page.

The low-code builders I tested either can’t do this, or not easily;

even if they do give you document object access,

you have to call it in a page load event handler after fetching page data from the external API.

Role details

The role details page only includes a heading and properties table in the HTML body:

<h1 id="name"></h1>

<table></table>

The renderRole function uses the same approach as before,

but with its own renderProperty helper function for each row in the properties table:

// Populates the title h1, opening crawl paragraph, and roles list

const renderRole = () => {

// Adds a properties table row.

const renderProperty = (table, label, value) => {

const tr = document.createElement('tr')

tr.innerHTML = `<tr><th>${label}</th><td>${value}</td></tr>`

table.append(tr)

}

const personId = window.location.hash.replace('#', '')

fetchJson(`person/${personId}.json`).then(person => {

document.title = `${person.name} – Project role`

document.querySelector('#name').textContent = person.name

const table = document.querySelector('table')

renderProperty(table, 'Born', person.born)

renderProperty(table, 'Gender', person.gender)

renderProperty(table, 'Height', `${person.height} cm`)

renderProperty(table, 'Mass', `${person.mass} kg`)

renderProperty(table, 'Skin', person.skin)

renderProperty(table, 'Hair', person.hair)

renderProperty(table, 'Eyes', person.eyes)

})

.catch(renderError)

}

Implementation simplicity

The previous articles in this series used the same example application to build read-only information pages with low-code app tools. Meanwhile, this example application implements equivalent functionality (excluding logging in, to make authenticated API calls) in 70 lines of JavaScript.

Sometimes, you can have simpler information pages than an app builder, if you can write the code from scratch.