Choir rehearsal score locations

How to avoid wasting time telling singers where to start 2024-04-01 #music

Choir rehearsals feature many stops and starts, as conductors stop the singers to ask for something better. Efficient rehearsal relies on quick and accurate directions that avoid confusion.

Homophony

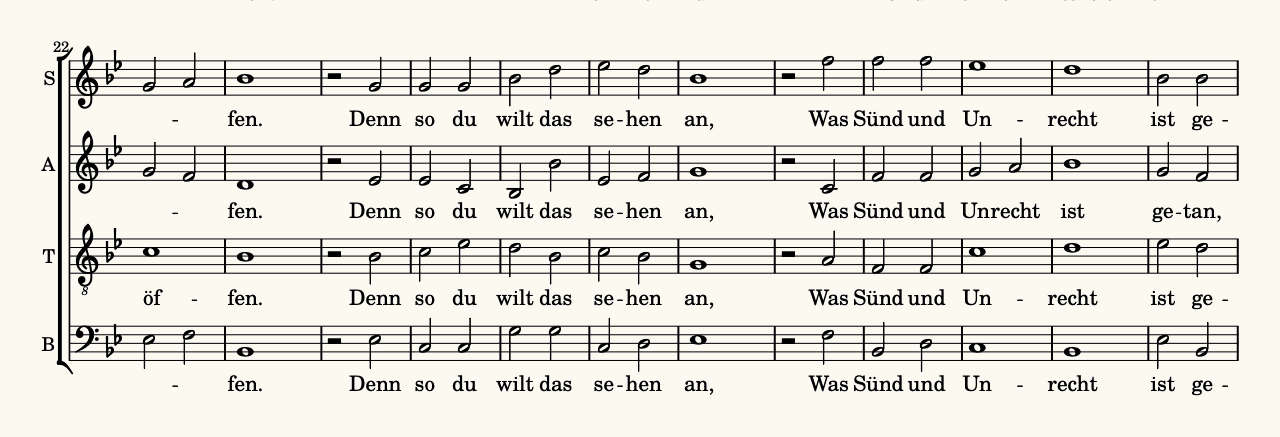

In hymns, everyone sings more or less the same thing at the same time (homophony). For example, in the sixteenth century chorale, Aus tiefer Not schrei’ ich zu Dir (CPDL #79638), four voice parts sing each word together:

With this music, the conductor can ask the choir to ‘start again from Was Sünd und Unrecht’, ignoring the tiny bar number ‘22’ (top-left).

Polyphony

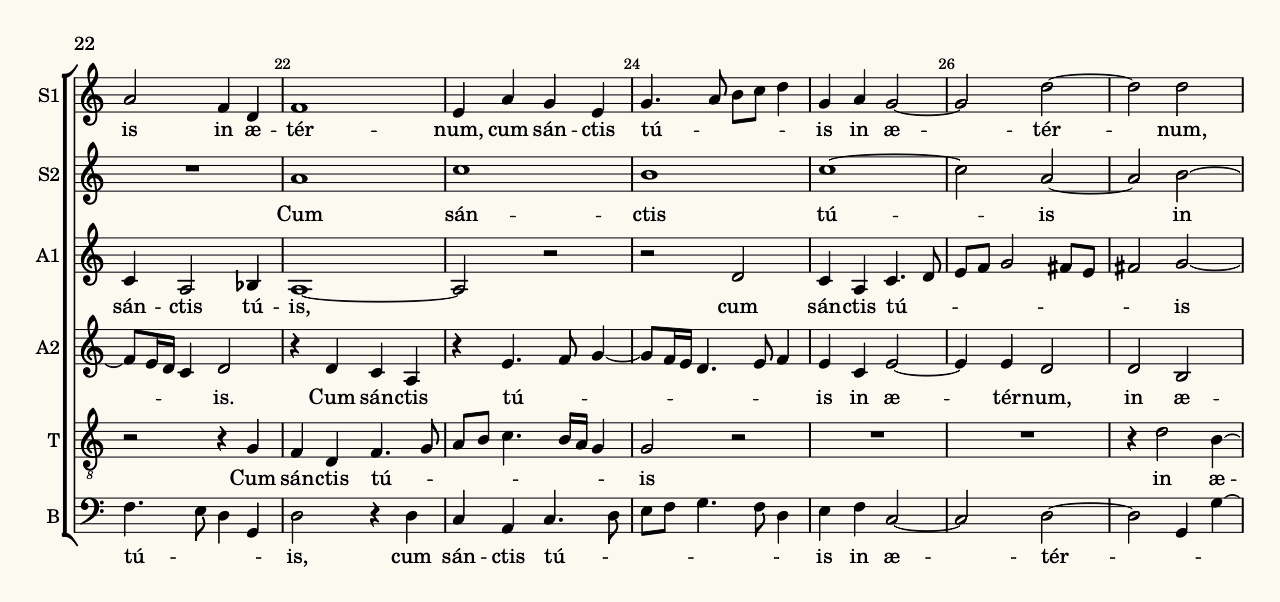

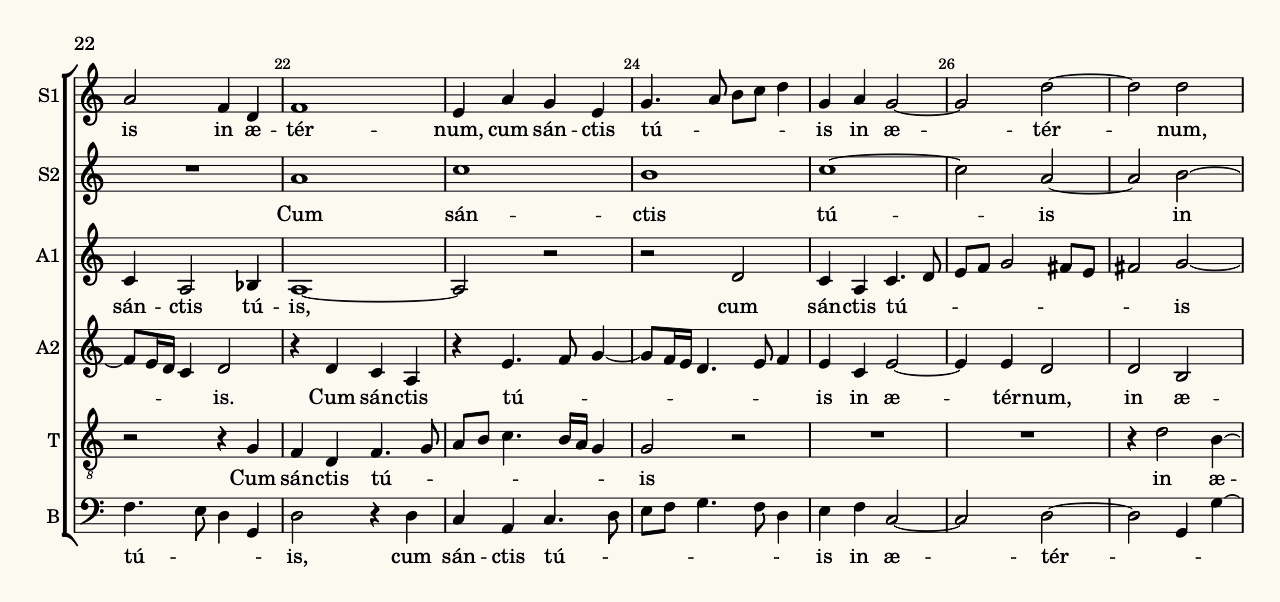

Renaissance polyphony makes it harder to find a convenient place to start, because different parts may sing the same text, but not together. For example, this excerpt from a Missa Pro Defunctis (CPDL #36844):

The conductor probably wants to start from where one of the six parts starts the text cum sanctis tuis. However, the singers don’t know which one.

Underlay

Chaos ensues when the conductor tells 24 singers, ‘let’s start again from cum sanctis’.

- Half the choir looks at the top three lines, and expects the second soprano part (S2) to start first, in bar 22.

- Several people heard someone say ‘bar 22’, but mistake the page number (top-left) for the bar number.

- The first sopranos (S1) focus on themselves, and expect everyone to start in bar 23.

- Someone still expects to start on the previous page, where cum sanctis tuis first appears.

- The tenors think the conductor wants to start at their entry (T) in bar 22, and only got it right because they only sing cum sanctis tuis once on this page.

Polyphony requires more helpful navigation.

Bar number and beat

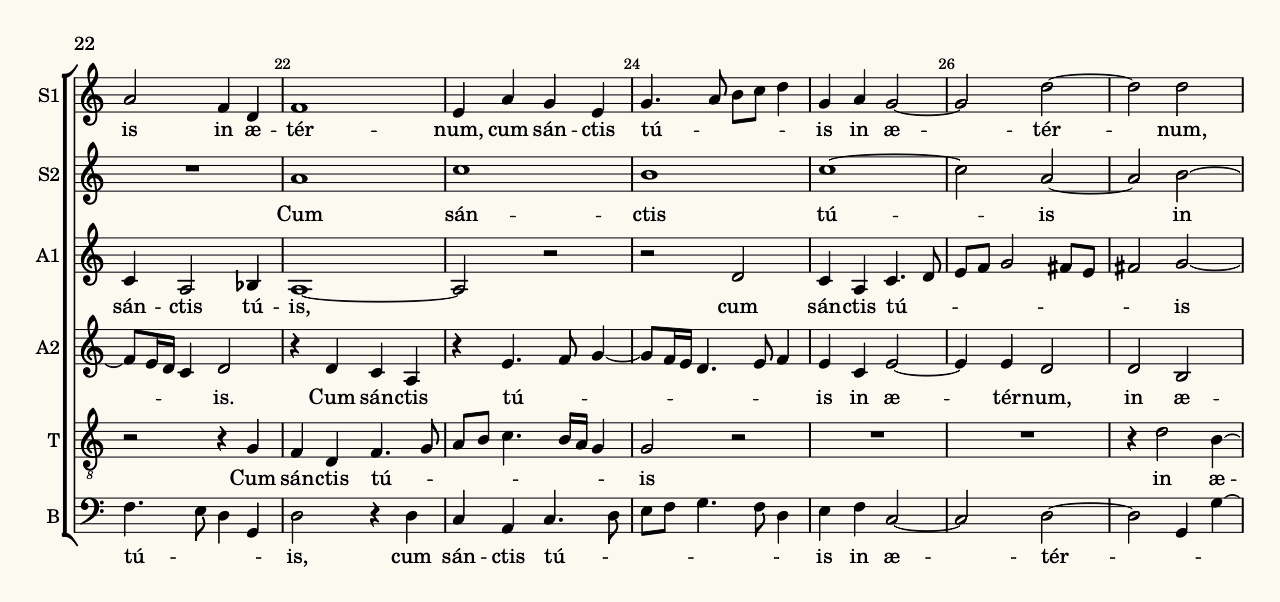

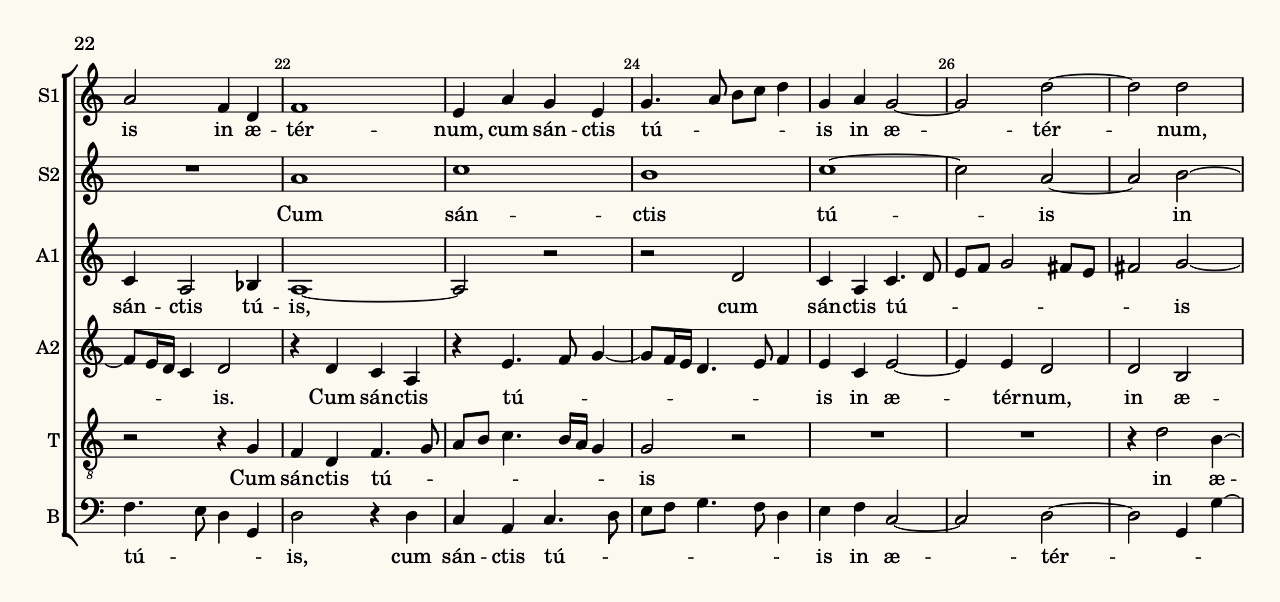

Bar numbers solve the navigation problem: the conduct asks the choir to start at bar 21, second beat:

The singers probably expect the conductor to count two beats in the bar in this style, not four. However, the conductor might still confuse them by asking for bar 22, meaning the upbeat before the start of the bar. The conductor should express their intent better.

Bar number and voice part

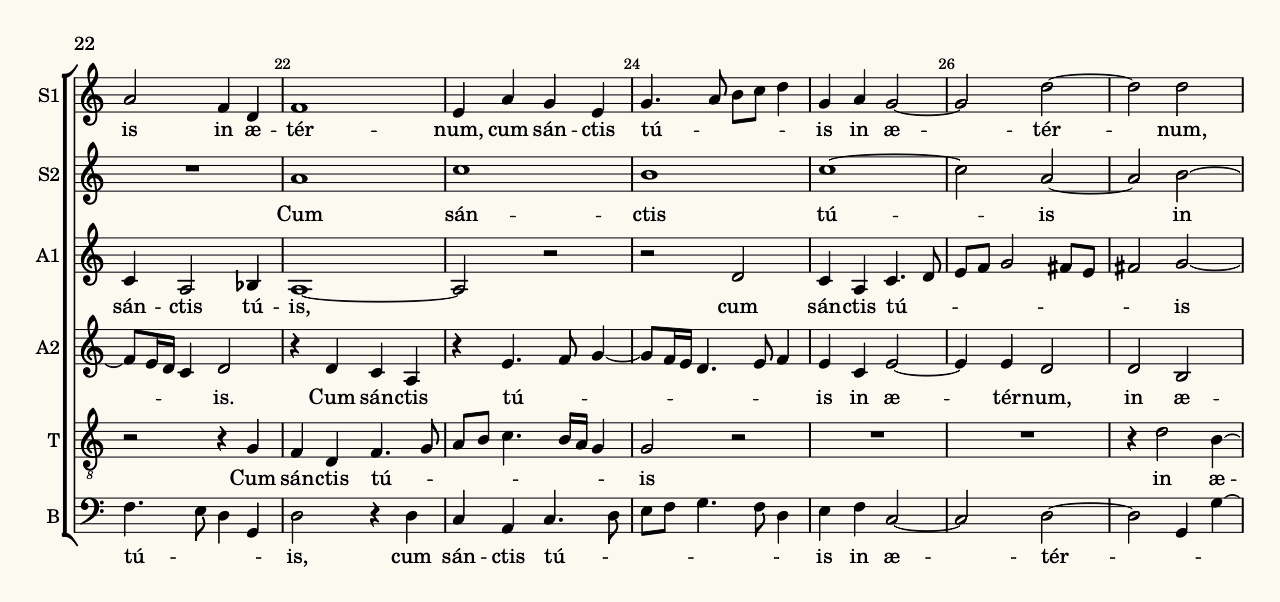

Referring to the tenor entry in bar 21 adds just enough redundant information:

Singers will easily see where the tenor part (T) starts a new phrase in bar 21.

Start of the system

A less conventional conductor might avoid the navigation problem by only ever picking up from the start of the system - bar 21 in this example:

Four parts begin at the start of the bar, and the others join in with the phrase cum sanctis tuis, starting with the tenor part at the end of the first bar. Singers may find this unmusical entry in the middle of a phrase more difficult, but they can get used to it, and it saves a lot of confusion.

Rehearsal mark

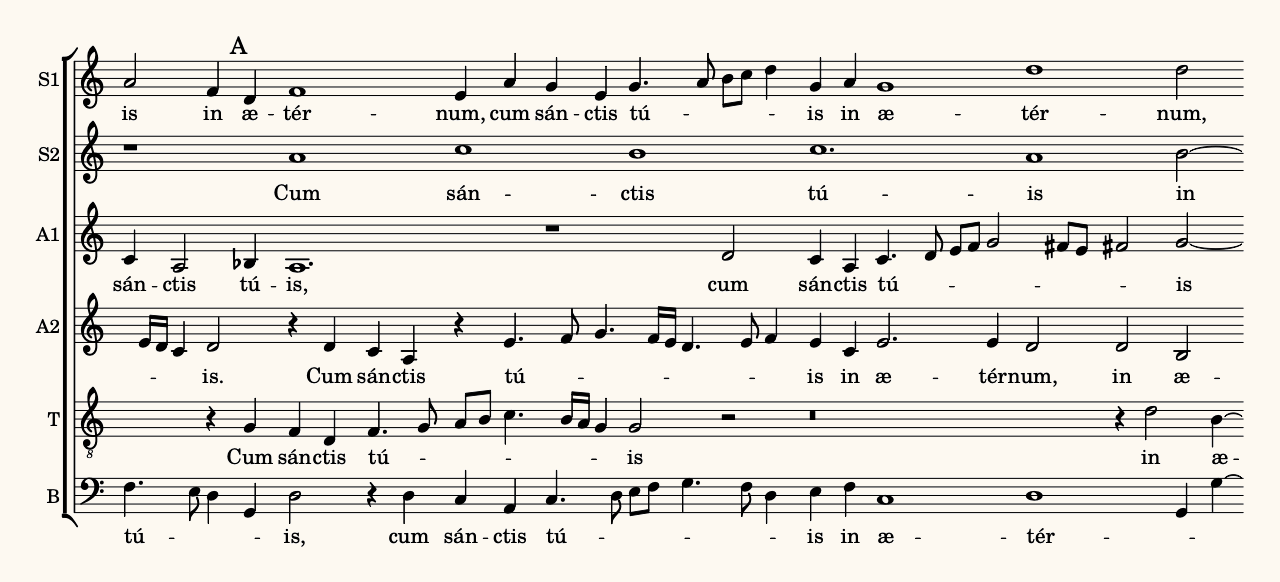

This sixteenth musical style pre-dates bar lines and bar numbers, which don’t seem to help all that much. Some conductors and singers prefer renaissance polyphony scores without bar lines:

Without bars, you navigate with rehearsal marks, such as the letter A. They reduce the possible starting locations to two or three per page, making them easy for singers to find when the conductor asks the choir to start from, say, ‘the tenor entry at A’. As in all good instructions, simple but explicit wins.