Brute-force modelling

When avoiding over-modelling feels like cheating 2022-06-28 #DDD

Pixar’s 2001 film Monsters Inc. achieved protagonist Sully’s realistic fur by simulating and rendering millions of individual strands of hair. This gave the animated character more detail than traditional techniques ever made possible.

A more musical equivalent of fur occurs in acoustic piano strings’ sympathetic resonance, where certain piano strings resonate quietly when you play other notes, adding depth to the overall sound. Modern digital pianos model individual resonating strings, and play string resonance sounds along with the notes you play.

These modelling examples suggest an alternative way to deal with a complex world in which conventional models fall short. Delivery addresses, for example, turn out to have more complexity than you might hope.

Non-numeric house numbers

In Modelling universal values, I present several examples of non-numeric numbers, starting with house numbers. Despite the word numbers, they deviate from ordered, sequential, numerical values.

The houses on this short road to the beach on the South coast of England, where I lived as child, all have names instead of numbers. The photo shows the first house on the right, where I lived: The Boat House. Coincidentally, we later moved to another street a few hundred metres away where houses on one side of the road have consecutive numbers. I lived across the road, where all of the houses have names.

Brute-force delivery addresses

Strange house numbers, and other complications, lead to common mistakes when capturing and storing UK addresses. Instead of dealing with every single edge case, you can instead adopt the UK’s brute-force solution - the PAF.

The Postcode Address File (PAF) solves the difficulty of modelling UK delivery addresses by ‘simply’ listing all 30 million or so of them. This effectively reduces a potentially scary delivery address model into a single-value enumerated type, linked to standardised locality/town names and post codes. Instead of asking people to enter their address, you can instead ask for their post code, and then have them select their PAF entry from the post code’s list, typically around 15 addresses.

Non-consecutive house numbers

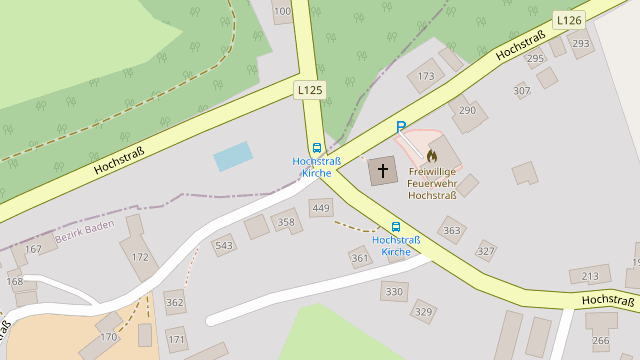

At DDD Europe 2022, I met an Austrian developer who offered an even better example of misbehaving house numbers. The village of Hochstraß, 30 km West of Vienna, in Austria, has chronological house numbering. Addresses number houses in the order of construction, regardless of their location in the village.

The only reasonable way to model this, as seen on OpenStreetMap, positions each house number individually. In the address model, only the village name relates these houses to each other.

In general, interpolating house numbers between the addresses at street corners only works for some streets in some cities. While some applications may need this optimisation, it doesn’t always work. In the end, mapping street addresses requires brute force: mapping every single address.

Brute-force modelling

Modelling information, and the world in general, helps us make sense of software products’ data. This works until it doesn’t, when our attempts to model increasing complexity fail to capture the real world’s messiness.

Sometimes, we achieve realism with brute-force modelling. And occasionally, instead of modelling what possible values look like, we can instead list them all, however long the list.